Bio: Chris is from Yorkshire in the UK. He has just started working as a lecturer at Himeji Dokkyo University (April 2018), teaching a range of English classes from 1st to 4th year students. Before that, he worked as an ALT in Okayama Prefecture for 8 years for Interac and as a direct hire.

Contact: cooperchris17@gmail.com

Website: https://cooperchris17.wixsite.com/englinks (English Links for Language Learners – still very much a work in progress!)

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/chris-cooper-95589b47/

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christopher_Cooper22

The Teaching Reading module is being written by Rob Waring, who is one of the world’s leading experts in the field of extensive reading. You will learn a lot more than I can tell you working through his module, but for now, this is my little story of how I got into teaching reading and extensive reading at elementary school.

I was an ALT, teaching mainly in elementary schools, from 2010 to 2018. During that time, I completed my masters in TESOL, which got me interested in Language Acquisition, particularly researchers like Stephen Krashen, who is famous for his work on comprehensible input and ‘i + 1’ theory (Krashen, 1982). In basic terms, he said that learners will naturally acquire a language by understanding what is said to them and what they read. Ideally, their input should be slightly above the level they understand. I think this is what set me on the road to extensive reading.

Until recently, and possibly still the case in some schools, there has been a fairly strict speaking and listening only policy in the Japanese elementary school English classroom. We know the alphabet exists, we will learn the names of the letters in order, but don’t show it to the kids too much, it might scare them, and for god’s sake don’t let them try to read the words.

I can see the logic to this policy. Children learning their first language (L1) listen and speak before they read. This is preceded by an 18 month to 2 year ‘silent period’ from birth. Some approaches, such as the original form of Total Physical Response (TPR) (Asher, 2012) even advocate transferring the 18-month silent period to second language (L2) learning.

Also, if you speak with local people in Japan from an older generation, they often describe junior high school English of the past negatively, wishing they had more communication in the classroom as opposed to reading and writing only. The recent elementary school policy may be a reaction to this (although I have no real evidence to support this!).

Some researchers suggest teaching reading from day one of L2 learning (Furukawa, 2008), and whilst this may not be appropriate for very young learners in kindergarten or elementary school, the tide seems to be changing towards a more balanced approach including literacy from an earlier age. Recent materials from MEXT have included alphabet writing worksheets, phonics jingles and two digital picture books, which have now been incorporated into the 3rd and 4th grade textbooks. My concern is, this is not enough.

Most teachers of young learners would probably agree that some form of phonics is a good idea. The new We Can textbooks cover the main letter sounds from each of the 26 letters of the alphabet, plus /ch/, /sh/, /wh/ and the two /th/ sounds. This is a start, but there are around 44 sounds in the English language (Underhill, 2008) and other approaches are more attached to these sounds than single alphabet letters. Jolly Phonics, using the synthetic phonics approach adopted by UK primary schools, teaches the 42 main letter sounds of English (Jolly Phonics, 2018) in an order which enables learners to read words from the very early stages.

Whilst English could be described as phonetically opaque, meaning some words have irregular spellings, according to Adams (1990), around 80-90% of English words do have regular spellings. For me teaching phonics is essential, but how exactly should we do it? The door is wide open for more research into what kind of phonics is suitable for Japanese elementary schools and how it should be implemented in the curriculum.

We know that children learn language by focusing on the meaning (Cameron, 2001; Moon, 2000). Whilst learning how to read individual words can be helpful when reading road signs or shopping, both of these points are covered well in the MEXT textbooks I think, the goal or meaning of reading is surely reading longer texts, like articles, letters or especially for children, stories. The We Can textbooks include ‘Story Time’ and whilst some include rhyme, and may be like poems, they miss out key characteristics of stories, like being genuinely interesting, or having a twist at the end (Cameron, 2001). Whilst their redeeming factor is they may be easy to decipher, I doubt children will enjoy them.

In my last three years as an ALT, I found myself teaching at a ‘Special English Zone’ school, which was a normal public school, but had more English lessons than usual, as the rest of the country will from 2020. It also had a bit of an English budget and as I sat at my ALT desk, contemplating holes in MEXT textbooks, how I could get my students reading and other things, one of my colleagues asked me for any recommendations about materials we could buy…and my answer was graded readers.

I have always liked the use of picture books and have found that if you are friendly with the school librarian and ask nicely, they will sometimes get you some nice books, which you can read to your students, but this was the first time we had purchased books for the students to read themselves.

My approach to introducing the books was very top down, simply handing them over to students, initially having them read in pairs and telling them it doesn’t matter if you can’t understand all the words as long as you can just about understand the story. As books at this level have lots of pictures, most students could do this. I found the following rules to be helpful and popular with my students (based on Furukawa, 2006):

1. There is no need to look at a dictionary while reading.

(じしょはひかなくていいよ)

2. Difficult to understand parts should be skipped over.

(わからないところはとばす)

3. If a book is uninteresting or too difficult, stop reading.

(つまらなければやめる)

These rules seemed to relieve pressure and allowed many students to enjoy reading English books. During reading sessions, I would walk around to allow students to ask me how to read words they were struggling with, and I would encourage them to help each other too. I would observe if students seemed to be reading books at the right level for them, which was helped by checking the reading logs they were keeping, logging the titles of books, dates, a comment about each book and a rating from one to four on how much of the book they understood and how interesting they thought it was.

In the two years I tried extensive reading in elementary school, I found the level most appropriate for my students was level 1+ of the Oxford Reading Tree series and level 1 of the MPI Building Blocks Library. Some students were able to read slightly higher levels than that, around levels 2 and 3 of the same series.

Handing over books to students in this way can be quite a steep learning curve for them, and with this in mind, at my school we also did other activities to try to ease the path into reading. One was phonics, which I have already discussed, and another was getting the 5th and 6th grade students to read texts they were already very familiar with orally.

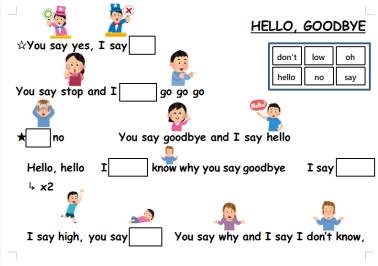

Specifically, one was the monthly song. Most elementary schools will sing a song every month in Japanese, but my school sang one in English, which the kids would learn by heart by the end of the month. We would always put a big illustrated print out of the song lyrics on the whiteboardwhiteboard, without drawing too much attention to it. Then at the end of the month I would prepare individual copies of the lyrics for the 5th and 6th grade students to read, fill in the missing words, or I would cut the lyrics up, to be rearranged like a puzzle. Here are some examples:

I always remember this one, because one student pointed at the word ‘knock’ and said, ‘Chris, Chris, this word is k-n-o-c-k, right’. Even though he knew the word orally from the story, he was reading the /k/ and /n/ separately. This was probably related to his phonics knowledge, but it made me think this kind of approach was helpful because there is less reading pressure when you read something you know, like a very young L1 learner might start reading a nursery rhyme or picture book that has been read to them many times. Where there is less pressure, there is possibly more room for noticing things about how the words are written. In this case, it was a good opportunity to share with the class that in English, when words start with ‘kn’, we don’t pronounce the /k/.

In March 2018, I asked students who had been reading graded readers for almost two years three questions (answers in brackets):

Did you enjoy reading graded readers?

1. No (0) / 2. A little (5) / 3. Quite enjoyed it (7) / 4. Enjoyed it (3)

Do you think reading graded readers is useful for your English education?

1. No (0) / 2. A little (5) / 3. Quite useful (1) / 4. Useful (9)

Would you like to continue reading graded readers in junior high school?

1. No (0) / 2. A little (6) / 3. Quite (6) / 4. Yes (3)

Whilst my sample was very small, only 15 students in this class, I think what these results show is that these learners thought reading graded readers was beneficial for them. Also, none of them were completely averse to reading English books, which I thought might be the case when I started using graded readers. I would like to see more teachers try reading in their 5th and 6th grade classrooms around Japan, to see if their learners find them to be beneficial too. Linking elementary school to junior high school reading with the interesting reading material that graded readers provide, could make more learners interested in reading, rather than only reading the textbooks’ often dense and difficult to decipher texts.

References

Adams, M.J. (1990) Beginning to read: Learning and thinking about print. London: MIT.

Allen-Tamai, M. (2013). Story Trees. Tokyo: ShoPro.

Asher, J. J. (2012). Learning Another Language Through Actions (7th ed.). Los Gatos, California: Sky Oaks Productions, Inc.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Furukawa, A. (2006). SSS Extensive reading method proves to be an effective way to learn English. Retrieved from http://www.seg.co.jp/sss/english

Furukawa, A. (2008). Extensive reading from the first day of English learning. Extensive Reading in Japan 1(2). 10-14.

Jolly Phonics. (2018). Teaching literacy with Jolly Phonics. Retrieved from http://jollylearning.co.uk/overview-about-jolly-phonics/

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and Practices in Second Language Learning. Oxford: Pergamon.

Moon, J. (2000). Children Learning English. Oxford: Macmillan-Heinemann.

Underhill, A. (2008). Interactive phonemic chart: British English. Retrieved from http://www.onestopenglish.com/skills/pronunciation/phonemic-chart-and-app/interactive-phonemic-chart-british-english/

Don’t have any ideas? We have a list of topics to write about that need a writer. Email in your interest to write and we can set you up.

For upcoming blogs see the blogs tab here: http://www.alttrainingonline.com/blog.html