Bio: My name is Daniel Pearce, and I am currently working as a teacher-researcher at Kyoto Notre Dame University. I was an ALT in several high schools of the Shonai region of Yamagata Prefecture between 2008 and 2013. During my time in Yamagata, I committed myself to studying Japanese and kanji and, beginning with the methods laid out in this blog post, obtained level pre-1 of the Japan Kanji Aptitude Test in 2011. My current research interests include team teaching and plurilingual and intercultural education.

If you’re ALTing in Japan, needless to say, learning the Japanese language is a surefire way to better engage with schools and communities, and success in language learning can lead to much more fulfilling personal and professional lives. For those of us who have not previously acquired a foreign language (as I hadn’t), it also helps us relate better to what our students are going through. But of course, in learning Japanese, there is that one dreaded hurdle… kanji. How can we be expected to remember 2000+ commonly used characters, the majority much more complicated than any character in the alphabet (assuming English-speakers) we know?

The struggle of learning the kanji can seem so insurmountable that many eventually give up trying to master them, and try to get by with just the kana, a number of useful kanji they remember or use often, and acquiring their Japanese through speech. Of course, there are many approaches to learning languages, but when it comes to acquiring proficiency in Japanese (here meaning the ability to engage with more complex topics), knowledge of kanji is absolutely essential. In this post, I will quickly outline why kanji knowledge is essential, and also how the hurdle of learning upward of 2000 characters can be broken down into a (relatively) painless process.

Firstly, why are kanji necessary? Well, because Japanese is absolutely loaded with homonyms. For example, since I want to introduce an effective means for learning kanji, let’s take the word ‘effect,’ which in kana is こうか (効果). That’s all well and good, but こうか can also mean school song (校歌), expensive (高価), coin (硬貨), a descent or fall (降下), an overhead structure (高架), an engineering department (工科)… and that’s just the start. The reason for this seemingly absurd number of homonyms is historical in nature, as the readings were imported alongside the characters themselves. Space precludes a full discussion of this, but I do expand upon it in a recent article on plurilingual education (see Moore, Oyama, Pearce & Kitano, 2020).

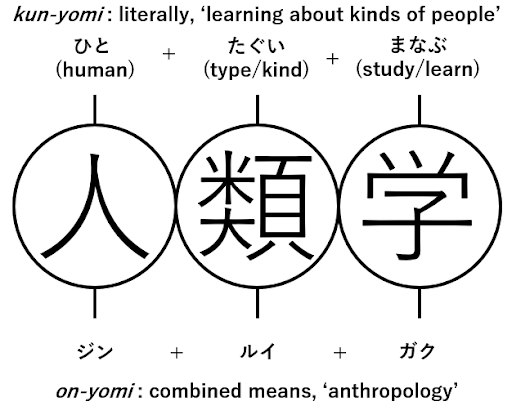

The fact that kanji has both (originally Chinese) on-yomi as well as uniquely Japanese kun-yomi readings also proves a headache for many learners, although this unique aspect of the Japanese language can actually make vocabulary acquisition easier. To take an example, even if you know the word “anthropology” in English, you wouldn’t necessarily know that it is a combination of the Greek anthrōpos (human) and logy (which has come to mean discourse/science). An elementary school student would also be unlikely to know the word, nor be able to readily infer its meaning. The opposite is true in Japanese: Take the figure for anthropology below (example inspired by Suzuki, 1977), upon first reading of which a Japanese schoolchild would be able to understand. This linking of sound with ideographs has helped me on occasion, too; in a rather unfortunate anecdote, I remember visiting the doctor with intense abdominal pain, and my diagnosis was a word I had never heard before, but instantly understood: nyorokesseki (尿[urinal], 路, [tract], 結 [crystalline], 石[stone]). Yep, kidney stones. Ouch.

This is all well and good for Japanese students who spend years studying kanji at school, right? Japanese students grow up and go through schooling, learning about the concepts that the kanji represent while learning the kanji themselves. Adults, on the other hand, have at least one leg up on them – we already know the concepts. We just need to get the characters down. One approach to studying kanji then, is to first separate them from other aspects of language study. Perhaps the first person to do that in a systematic way, back in 1977, was James Heisig who authored Remembering the Kanji, the book I used to launch myself to kanji proficiency (at the time in its 5th edition).

Heisig’s method is relatively simple – he ascribes one English meaning to each kanji, breaks them down into radicals, each with their own meanings, which are put together as pneumonic ‘stories’ to ease memorization (Heisig explains it better in his introduction, included in a sample of the book posted online by Nanzan University), which are which are then ordered in an easy-to-follow manner. Combined with automated flashcard software such as the freeware Anki (although there are many others), learning the meaning and how to write the roughly 2,000 characters is possible in a couple of months (I recall it took me about a month to input all of the kanji into the Anki software – although I did spend a couple of hours a day for that month to do it).

Unfortunately, learning to read the kanji is another matter, although once you have the meanings down, it becomes an aid to engaging with Japanese text you might not be able to pronounce yet. For the readings, I stuck to the Anki software, adding in as many Japanese sentences as I could, and learning the readings through osmosis. It did take a lot of effort, but was well worth it – I can still remember how fun it was to sit the kanji kentei at school alongside my students! As ALTs, the large part of our job is to teach language, but it’s also important to demonstrate that language learning goes both ways. Really engaging with kanji is a life-changer, as it opens you up to a world of literature and experiences, and goes a long way to legitimizing yourself as a language professional, too.